The arid landscape of Western United States (Utah), photo by author.

The arid landscape of Western United States (Utah), photo by author.

The first European settlers were quick to discern what can still be seen today as the United States’ greatest asset: the land. The American West in particular strikes the eye of the visitor with its vast and apparently boundless landscape, which was soon seen by settlers as an opportunity for exploitation. The conflicts arising from cattle ranching are directly related to how open spaces are managed in the American West. These managerial conundrums are both social and political in nature. Furthermore, the biophysical environment typical of the Western United States is at odds with the biological needs of the animal exploited. Cows are invasive species whose biological requirements outweigh the natural resources available, specifically water and forage. This industry, encouraged by a highly capitalistic nation with heavy consumer demand for beef, is supported by various political actors. These include the U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM), whose role is to manage public land, and Wildlife Services, a branch of the US Department of Agriculture that slaughters predators and pests on behalf of livestock ranchers. The extensive occupation of public land by cattle has led to the destruction of pristine wilderness areas. Using landscape symbolism and a political ecology perspective, we can look further into the environmental issues arising from overgrazing on public land. It is a conflict as old as the settlement of the West, pitting a powerful private industry against the interests of the American public – which is to say, against every American citizen, the collective owners of the public lands.

Focusing on the “symbolic landscape” allows the issue of cattle ranching in Western United States to be better understood. A “landscape” is the symbolic environment created by the human act of conferring meaning on nature and the environment. Landscapes reflect the self-definitions of people within a particular cultural context. In this sense, each landscape can be transformed symbolically to reflect this identity. Landscapes are visualized by people through a “special filter of values and beliefs” (Greider and Garkovich: 1994), and so people project their own meaning of the environment onto a specific landscape. Because each culture can confer meaning to the environment, the theory suggests that all ideas of nature are equal. However, these ideas are not equal for there are physical properties proper to each aspect of nature. In this sense, landscape symbolism adopts a radical constructivist (and essentialist) view because it undermines the influence of the environment as an independent causal force. There are natural forces we cannot contest. The role of power in renegotiating landscape is related to political ecology. Paul Robbins (1998) describes political ecology as “empirical, research-based explorations to explain linkages in the condition and change of social environmental systems, with explicit consideration of relations of power.” “Power,” in Robbins’ view, is the capacity to impose a specific definition of the physical environment, one that reflects the symbols and meanings of a particular group of people. There are three factors underlying this power: the ability to define what constitutes information; the control of this socially-constructed information; and the symbolic mobilization of support. In fact, “the environment is an arena of contested entitlements, a theater in which conflicts or claims over property, assets, labor, and the politics of recognition play themselves out” (Peluso and Watts 2001:25).

Western livestock ranchers, with their associated culture of “cowboyism,” have effectively defined and controlled the information available to the public about the Western lands, and thus have been able to mobilize public support for that culture’s continued domination of the landscape.

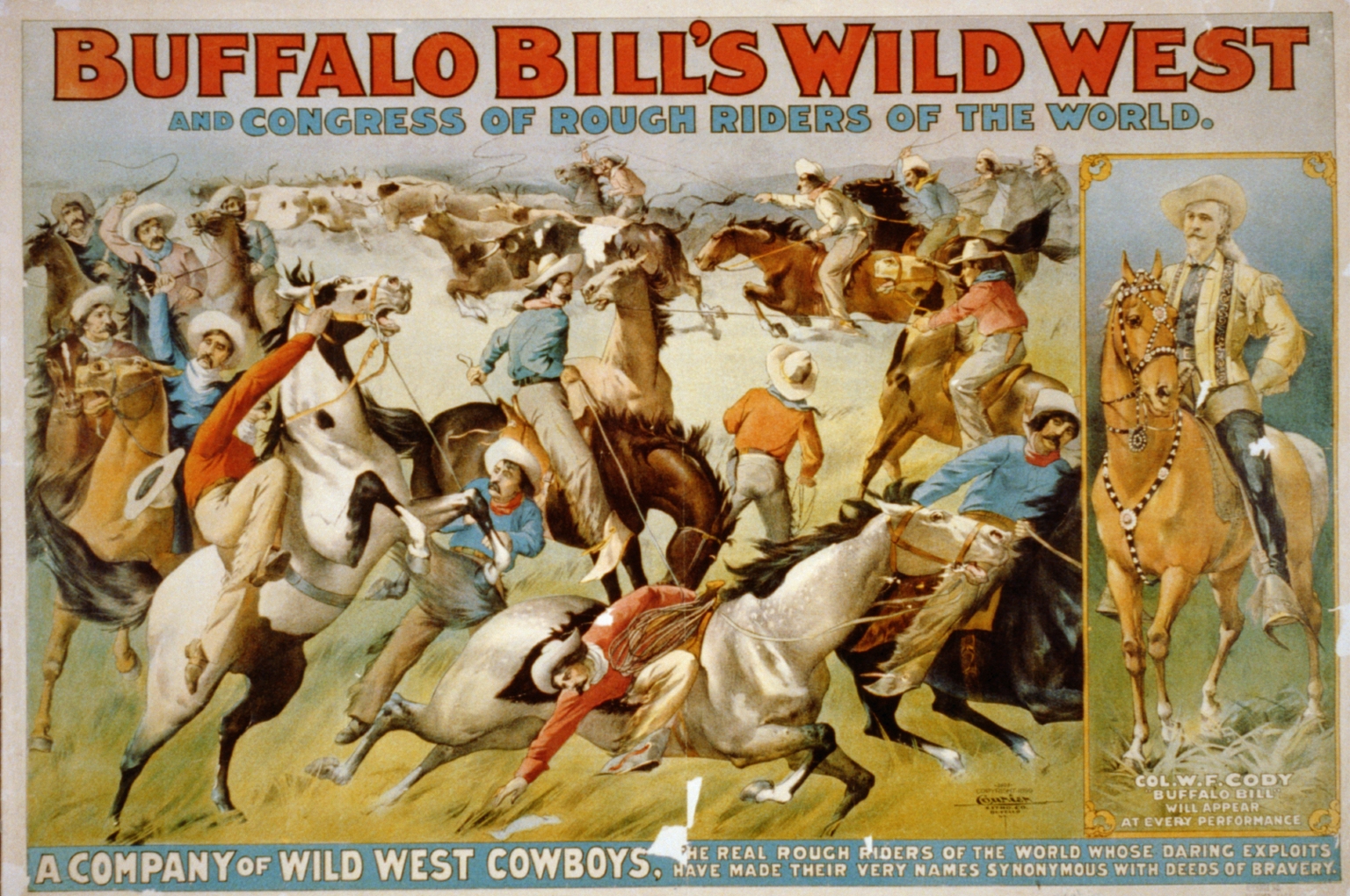

Understanding the concept of public land is essential to grasp the conflict between cattle ranchers and environmentalists. This land, mostly found in the Western states of Utah, Idaho, Arizona, Nevada, New Mexico, Wyoming, and Colorado, is held in trust for the public by the federal government. Yet hundreds of millions of acres are leased to ranchers for livestock grazing, and ranchers have claimed these leased parcels as a property right. Federal land managers have too often disseminated this false concept of a property right on public lands. The reason they do so is deference to the livestock industry, which is politically powerful. So the ranchers effectively define, through their capture of government regulators, the terms of public discussion about public lands. In part their power lies in the long history of ranchers on the landscape. Open range livestock ranching was established in Texas in the 1700s by Spanish settlers, and by the middle of the 19t h century it was expanding rapidly across the entirety of the American West. By the 1860s, beef had become a popular food, driving an increase in demand for cattle raising. The development of national railroad networks allowed open range Western cows to reach Eastern markets where there was high demand for beef. At the same time, the cowboy became associated with the elimination of Native Americans and the subjugation of the frontier for the establishment of “civilization.” The culture of ranching thus became an intimately American phenomenon. The cowboy, romanticized in books, films and on television, was now a heroic figure: austere, independent, self-reliant. This mythology of the cowboy was of course nowhere reflected in historical fact.

Poster of vaudeville performance showing cowboys and the rounding up of their cows: example of the popularization of cowboy culture (Source : Courier Litho. Co., Buffalo, N.Y.)

Poster of vaudeville performance showing cowboys and the rounding up of their cows: example of the popularization of cowboy culture (Source : Courier Litho. Co., Buffalo, N.Y.)

The culture of cowboyism does have a particular landscape symbolism, as reflected in a 2013 study by Roslyn G. Brain et al. which looked at the “environmental identity” of a group of 25 “rancher families.” The study found that ranchers see the land not as an ecosystem but as an opportunity for economic gain. “[E]specially with an agricultural audience,” the study noted, “words too strongly associated with environmentalists can create a complete communication block.” The survey comments made by the interviewees included: “I would never ‘worship’ land or nature, it is for providing food for people (the most important created being on Earth) it is my way of making a living. It is my gift and talent, what I was created to do to maintain a living;” ”the EPA, environmentalists, animal rights, tree huggers, and greenies will be the downfall of the USA”; and “I am a conservationist but not a ‘wild eyed’ environmentalist. I believe nature’s resources are for use but not abuse.” This attitude clearly reflects a powerful and ancient ideology of Western thought as expressed in the Book of Genesis in the Bible, which states unequivocally that nature is for man’s exploitation and that nature under the control of human beings will always progress toward a “better” state of being. It is crucial to move away from such an essentialist vision of the natural world in the age of environmental degradation as a worldwide concern.

Livestock agriculture is the leading cause of most prevailing environmental degradation on the public lands of the American West. This includes the acidification and soil depletion of the already fragile ecology of the Great Plains, the endangerment of native species, and greenhouse gases emission. Raising livestock in the US consumes 34-76 trillions of gallons of water a year. This statistic is communicated among other striking numbers in the 2014 movie Cowspiracy, directed by Kip Andersen and Keegan Kuhn. The movie addresses the almost entirely unchallenged issue of the ecological effects of cow grazing. Andersen approaches leaders of environmental nonprofit groups such as Greenpeace and is met with silence upon the mention of animal agriculture. The subject, as Andersen finds out, is taboo among the environmental groups. This destruction not widely discussed among the public exemplifies a politically defined and controlled “symbolic” representation of this landscape. The public has been led to believe that the cowboy is a “steward” of the land, his cows beneficial to the landscape. Furthermore, the Bureau of Land Management divulges distorted information on grazing: “The unregulated grazing that took place before enactment of the [1934] Taylor Grazing Act caused unintended damage to soil, plants, streams, and springs. As a result, grazing management was initially designed to increase productivity and reduce soil erosion by controlling grazing.” In fact, grazing continues in an unregulated fashion and the result is environmental damage.

Logo of the Bureau of Land Management

Jerome E. Freilich et al. (2015) identify six ecological concerns related to livestock grazing in the Great Plains. Among those are the predator and pest threats to cows grazing on open rangeland. “Problem” animals — including, for example, coyotes, bears, black-tailed prairie dogs — are killed ostensibly to protect cows and their forage supply. The paper also notes the “truncation of the food web” occurring, for instance, as the bison territory is now occupied by cows whose carcasses are not left to rot on land for scavengers and decomposers to feed on. Without these nutriments unique to decomposing flesh, animals such as the California condor or the American burying beetle have now reduced their range and have been placed on the federally-managed endangered species list. The threat to biodiversity from livestock grazing correlates with the introduction and spread of nonnative plant species (mostly invasive weeds) and diseases. This disturbs the entire ecology of the arid Western desert in which native species have struggled through millions of years of evolutionary trial and error to adapt to such a harsh environment.

The Western United States is today under imminent threat from water depletion. Residents of states like California, Nevada, and Utah, though aware of the scarcity of water resources, fail to recognize the livestock industry as the largest and most wasteful user of water as well as the prominent cause of the disruption and pollution of aquatic systems. Debra L. Donahue, an ecologist and professor of law at the University of Wyoming writes “according to the Department of the Interior, BLM riparian areas are in their worst condition ever; the dry uplands have not improved under BLM management, and “[w]atershed and water quality conditions would improve to their maximum potential” if livestock were removed from public lands.” (2015: 724) This is due to the colossal amounts of water needed for cows to drink and to grow their forage in an arid region.

The ranchers’ domination of the landscape has become especially controversial among environmentalists who strive to protect wilderness areas on public land. Wilderness areas are often public lands which remain relatively pristine, untouched by humans. The Wilderness Act, passed in 1964, defines a wilderness area as “an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.” In this sense, wilderness areas are a sanctuary for evolution to follow its course, where natural processes remain unspoiled by human footprint. The Act further defines wilderness as “an area of undeveloped Federal land retaining its primeval character and influence without permanent improvements or human habitation, which is protected and managed so as to preserve its natural conditions.” The Wilderness Acts has additional value in its rather socialist approach as Congress secured “for the American people of present and future generations the benefits of an enduring resource of wilderness.” Congress is responsible for changes in the status of these areas found on federal public land. U.S. Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and National Park Service are responsible for its preservation and, where needed, for the restoration of its pristine character. Although there have been successful stories of rehabilitation such as the reintroduction of wolves in Yellowstone National Park, the occurrences of biodiversity loss far outweighs these improvements. Unfortunately, environmental degradations are mostly caused by the presence of cattle on these wilderness areas.

For the American citizens who find meaning and importance in the conservation of our natural environment, it is pivotal to understand the extent of the subsidization of the cattle industry by the federal government. A recent analysis (2015) finds that U.S. taxpayers have spent more than $1 billion over the past decade on public land grazing of cows and sheep. In 2014 alone, taxpayers spent $125 million in grazing subsidies on federal land. The federal government thus supports the landscape symbolism so long attributed to the West’s culture of cattle ranching. There are other indirect costs of those livestock agriculture subsidies, including the operations of the USDA’s Wildlife Services , which kills tens of thousands of native carnivores which are believed to represent a threat to livestock. The federal government also budgets hundreds of millions of dollars a year for the suppression of wildfires caused by invasive cheatgrass spread by cows grazing in unadapted environments.

The symbolic transformation of the Western public lands into places of resource exploitation must be redefined. The destructiveness of the livestock industry on a local and global level further justifies the need for new symbolic transformation: the land as a place for wild things — plants and animals — to be free and self-willed. For this transformation to be successful it is necessary to challenge the political forces in the definitions of land in the Western United States.

This article was written by Léa Barouch, Master’s student in the “Museology of Social and Natural Sciences” specialty at the Muséum national d’histoire naturelle.

Barber, Nancy L. 2009 “Summary of Estimated Water use in the United States in 2005.” US Department of the Interior, US Geological Survey

Brain, Roslynn, T. Irani, and M. Monroe. 2013. “Researching and Communicating Environmental Issues Among Farmers and Ranchers: Implications for Extension Outreach.” The Journal of Extension 51 (3): 3FEA4.

Donahue, Debra L. 2005. “Western grazing: The capture of grass, ground, and government.” Envtl. L. (35):721-1095.Freilich, Jerome E., et al. 2003. ”Ecological effects of ranching: a six-point critique.” BioScience 5 3 (8):759-765.

Starrs, Paul F. 1998. Let The Cowboy Ride: Cattle Ranching In The American West. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Additional Sources:

http://wilderness.nps.gov/faqnew.cfm

http://www.blm.gov/nv/st/en/prog/grazing/history_of_public.html

http://www.joe.org/joe/2013june/a4.php

http://www.blm.gov/wo/st/en/prog/grazing.html http://www.biologicaldiversity.org/news/press_releases/2015/grazing-01-28-2015.html http://www.biologicaldiversity.org/programs/public_lands/grazing/pdfs/CostsAndConsequences_01-2015.pdf