Nowadays, because of climate change, cities have to develop their green surfaces. In the following text, we will talk about “green cities” or “sustainable cities,” “green-cities,” and “eco-cities.” These cities must be sustainable by taking over the three pillars of sustainable development: by being economically viable, socially livable, and environmentally friendly. And so the cities must meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. The example of Berlin is interesting because it has already taken this phenomenon into account for some time. We will mainly focus here on the concept of biodiversity and on the elements of nature in cities that have a real advantage on human health (Fuller et al., 2007; Manusset, 2012).

Berlin has lots of parks, gardens, forests, family gardens, but also green fields. All these elements make Berlin a natural metropolis. With its 6,400 hectares of green space, Berlin ranks in the mean of European natural metropolises. Each inhabitant has 26 square meters of green space. This city has 430,000 urban trees and a vast peri-urban forest. It includes many wastelands, which are spaces reserved for “greening” the town. The city wraps around a central park called Tiergarten (210 hectares), which used to be a hunting reserve from the 17th century.

A view of a naturalistic landscape in Berlin Tiergarten. Source: Wikipedia Commons.

A view of a naturalistic landscape in Berlin Tiergarten. Source: Wikipedia Commons.

The countryside is very important in districts like Zehlendorf, Grunewald, Spandau, and Wilmesdorf. In fact, these spaces are inhabited by herds of wild boars. Furthermore, three suburban lakes (Wannsee, le Müggelse, and Tegeler) are natural reserves and also serve as water resources for Berlin. Projects of natural suburban parks are under development, like Naturpark in Barnim. This huge park located North East of Berlin covers 749 square kilometers, including 4,000 hectares that are integrated to Berlin. It aims to mix relaxation and leisure, to welcome tourists, while implementing a management policy promoting biodiversity.

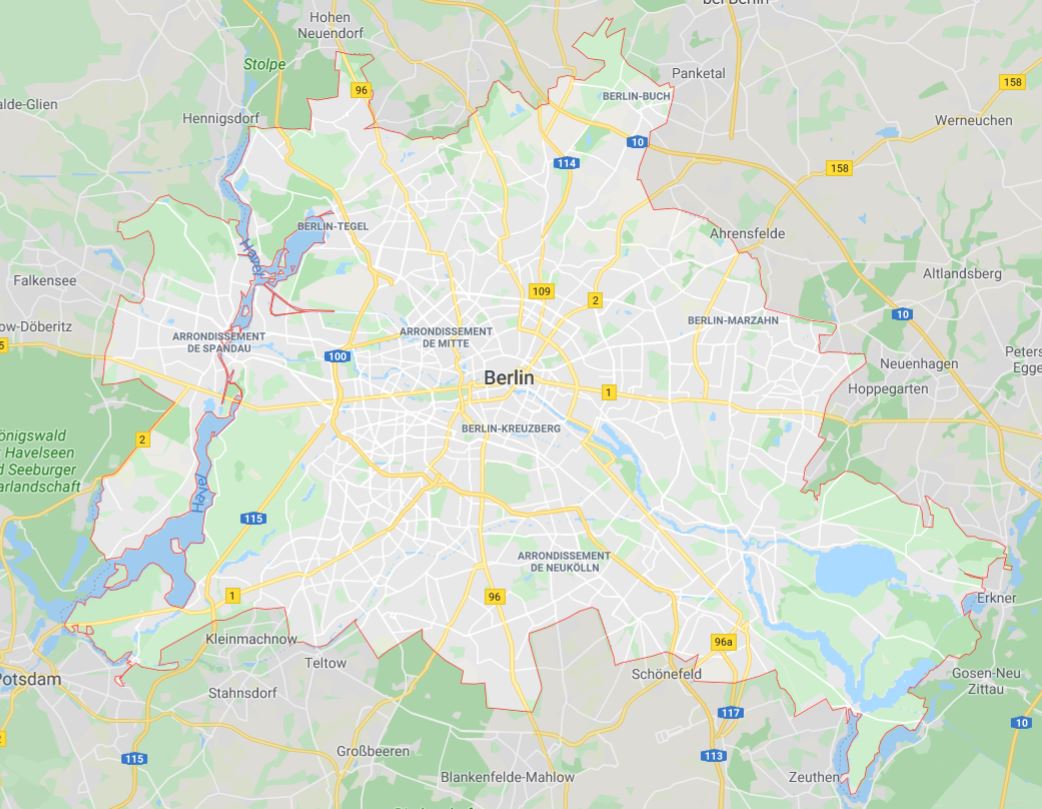

Map of Berlin metropolis. Source: https://www.actualitix.com/carte-de-berlin.html.

Map of Berlin metropolis. Source: https://www.actualitix.com/carte-de-berlin.html.

Brown fields and wild vegetation

Berlin hosts an abundance of wild flora. Free and spontaneous, it settles in nooks and crannies, railroad tracks, brownfield sites, planting pits, and building surroundings. Wild vegetation is accepted and tolerated for technical services of Berlin like landscaping principle. This flora is neither planted nor exploited. The maintenance of public spaces integrates the presence of vegetation, thus extensive management is widespread. The master plan for the green spaces of Berlin is marked by a double green belt of parks and a green cross that follows the axes of the rivers.

On the other hand, some towns develop environmental policies, like Paris, which do not benefit from urban biodiversity. Nothing replaces planting in real soil. In fact, Paris invests in many roofs and walls to “vegetalize” them. However, this form of revegetation works in opposition with the indigenous biodiversity. First of all, a minority of green roofs contains trees and shrub stratums. In ecology, the driving principle is the presence of different stratums. This allows insects and little mammals to circulate. Those woody stratums are a refuge, a feeding and breeding ground for avifauna. Furthermore, the question of green walls is controversial. In fact, those structures host only exotic plants. Consequently, these environments have a different biodiversity. For example, exotic species attract a different fauna, which competes with the local species.

In conclusion, a green city must have a maximum of green spaces to meet the need for biodiversity in its environment. It can be difficult for some cities, such as Paris, to maximize open ground spaces because of the lack of space. So the greening of buildings, thanks to walls or green roofs can be an attractive compensation even if it tends to reduce local biodiversity. Each city must reach a consensus to increase its biodiversity.

This article was written by Benjamin Terrasse in collaboration with Alexane Duveau-Chipaux, and Morgane Castellini all Master’s students in the Museum’s “Biodiversité et Aménagements des Territoires.”

Bibliography:

FULLER R. A., IRVINE K. N., DEVINE-WRIGH P., WARREN P. H. AND GASTON K. J., 2007, “Psychological benefits of greenspace increase with biodiversity”, Biology Letters 5, 5 p ; DOI : 10.1098/rsbl.2007.0149

Förderverein Naturpark Barnim e.V., 2019 “Das Projekt” [Online] [Accessed June 09, 2020]. URL: https://www.naturimbarnim.de/seite/382346/das-projekt.html?browser=1

MANUSSET S., 2012, “Impacts psycho-sociaux des espaces verts dans les espaces urbains”, Développement durable et territoires, Vol. 3, n° 3 [En ligne] [Consulté le 31 mars 2020]. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/developpementdurable/9389