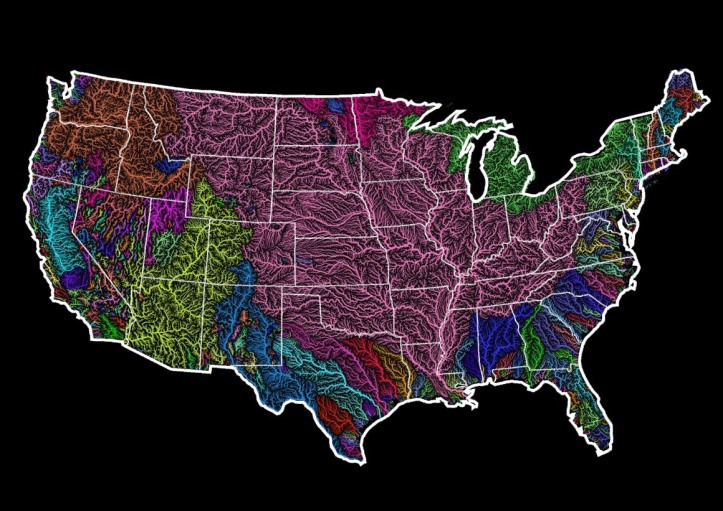

Watershed map of the United States & Cascadia by Szucs Robert.

Watershed map of the United States & Cascadia by Szucs Robert.

The likely path: urban sprawl

Within 30 years, world population will increase by a third, and there will be 9 billion people on Earth in 2050. According to the FAO (Food and Agriculture Administration), this demographic inflation will be paired with an increase in urbanisation, and two thirds of humanity will live in a city in 2050, against 55% today. Amongst the two more billion humans living on Earth in 30 years, half of them will live in a slum. As a result, empirical results suggest that, without effective policy interventions, urban sprawl could be the dominant urbanization pattern. It leads to the extension of cities into the countryside. Thus, it creates a lot of negative environmental and social impacts (1). Such rapid and negative urban development presents challenges to spatial planning. Urban densification and bioregionalism could represent two urban alternatives while they adhere to two complete different paradigms.

Densification, an apparent solution

In science and policy-making, the need to manage urban sprawl and its manifold negative consequences by promoting compact urban development is widely accepted. Urban densification, by concentrating inhabitants and consequently their travel and dwellings, and stopping the progress of the city into agricultural and natural lands, seems more desirable. But to what extent can urban densification be a solution?

One could reasonably question the sustainability of urban densification. Since contemporary economic growth of cities is closely associated with growth in the volume of buildings and infrastructures and since urban population keeps increasing (by 2% per year), maintaining the size of cities seems to be a real challenge. Moreover, facing climate change and the ecological crisis involves a lot of measures difficult to put in place in very dense cities but easier in spacious green areas (2).

Bioregionalism, a new perspective

Maybe we need to rethink these questions on a different scale, with better integration of biodiversity and landscapes in our perspective. The concept of a bioregion could be an interesting alternative to explore. Bioregionalism is a recent concept that proposes a new way to think about our territory. It suggests a complete redevelopment of our territory, divided in bioregions, defined by natural characteristics. The community of a bioregion would manage economic and agricultural activities according to the cultural and natural characteristics and according to two main principles: people should live in balance with the environment and reconnect with localism, which means to pursue self-sufficiency (3). Such restructuration is undeniably attractive for the quality of life it could offer. This is also a resilient model in line with the measures we have to take to face climate change and to improve the state of conservation of biodiversity, which is crucial regarding what nature offers to our societies. This concept was defined by Peter Berg who advocated it through his Planet Drum Foundation. One of the bioregions that Californian militants proposed is the “Shasta Bioregion” in Northern California. It is bounded by the Pacific Ocean, the Sierra Nevadas, the Klamath-Siskiyous, south to San Francisco bay, and its “high priority” is “bringing back salmon runs,” according to what is stated on their website (https://www.planetdrum.org).

How to set up bioregionalism

Is bioregionalism a better alternative for the future, and how could we achieve this form of organisation? We could approach these problems on two levels, the first being at the institution and policy level, the second being at a more individual scale. In terms of institutions, the main question is how to build a bio-region, how to set it up, what they should include, and what their limits will be, which would certainly be a long term process. Actually, we could already have the tools to build the bioregion, or at least the basis, with our current administrative regions, which are more or less already based upon natural landscapes and borders (like mountains, rivers, lakes, forests). This shift to a bioregion model should be articulated by a change in our policies, but once again, we have a history, in France and Europe, of decentralization of the power of the state to the administrative regions. A good example of that would be the prospective model of 8 bioregions for the Île-de France, proposed by the Momentum Institute, based mainly on the actual administrative borders. A strong policy will be needed in order to decongest urban areas and install different communities with cultural and natural limits, which would probably be very complicated to determine. Moreover, land would be regularly transformed into agricultural areas, while soils are often polluted and unsuitable for cultivation in and around agglomerations. Thus, in practical terms, bioregionalism involves a solid strategy and the implication of many local actors that will make the project possible.

If we look at a more individual and private scale, bioregionalism would imply a real change in our way of life (how we consume food, how we travel, how we build houses and buildings) and require to rethink our needs. This leaves us with two main questions. The first, is to determine a model of institutions and policies that will fit the bioregion concept. The second, is to ask ourselves how we should change the way we live if we were to switch to that kind of organisation. Such shift probably means bioregionalism must become more than urban planning but a real social project, based on an active collaboration at different scales, if it aims to become the major way we plan our territory. Therefore, urban densification seems easier to apply and currently represents the best short term solution to avoid urban sprawl and improve everyone’s living conditions.

This article was written by Suzy Pensuet in collaboration with Alban Narbonne and Marion Le Bouard, all Master’s students in the Museum’s “Society and Biodiversity” specialization.

Bibliography:

(1) (2) Petter Næss, Inger-Lise Saglie & Tim Richardson “Urban sustainability: is densification sufficient?”, European Planning Studies,28:1, 146-165, DOI: 10.1080/09654313.2019.1604633 (2020)

(3) Berg, Peter and Raymond Dasmann, “Reinhabiting California,” The Ecologist 7, no. 10 (1977)

http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/wsfs/docs/Issues_papers/Issues_papers_FR/Comment_ nourrir_le_monde_en_2050.pdf

https://www.institutmomentum.org/bioregion-2050-lile-de-france-apres-leffondrement-le-rapport-i ntegral/