“One hundred compagnies are responsible for 71% of global green house gases (GHC) emissions since 1988.”

I bet you’ve already read, seen or heard a sentence similar to this one. But where does it come from, and what does it involve?

When the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP), in collaboration with the Climate Accountability Institute (CAI), published in 2015 its report entitled The Carbon Majors Database, its sole purpose wasn’t to throw shade at the private or state-owned companies listed in their papers, but rather to enlighten actual and potential investors on where they are putting their money, and at what risk.

Its goal was also to make the industrial sector of fossil fuels more transparent and to highlight its responsibility in climate change inducing GHC emissions.

Talking about responsibility, the report contains another simple statistic of tremendous meaning: 25 industrial corporations only are responsible for over 50% of global industrial emissions since 1988. It’s been proven that those emissions are large enough to have actively participated in climate change and all of its infamous consequences worldwide: climate migrations, food production discrepancy, destruction of fragile ecosystems and their inhabitants, and overall loss of biodiversity.

By the way, do you know why the CDP and the CAI focused on the year 1988? Well, that’s when the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was created, 33 years ago. This intergovernmental body of the United Nations produces reports on the causes and consequences of climate change on economy, nature and politics, which are then reviewed by governments. For example, the IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report has been a strong scientific contribution during the redaction of the Paris Agreement in 2015.

But back to the report: knowing that a few people with big means of production and-we assume, a lot of money-are harming the environment way more than the vast majority of Humanity united can be an unsettling, worrying, even enraging news.

But it’s not necessarily a bad thing: that means we only need to convince a few people to change their habits and the way they do business and product items to dramatically reduce GHC emissions. Another rather interesting news: all of the most polluting entities are part of the same industrial sector. Wanna take a guess of which one everything is about? Here are the 10 companies which let go the most part of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere between 1988 and 2015, according to the CDP’s report:

- China Coal 14.3 %

- Saudi Aramco 4.5 % (officially the Saudi Arabian Oil Company)

- Gazprom OAO 3.9 %

- National Iranian Oil Co 2.3 %

- ExxonMobil Corp 2.0 % (one of the world’s largest publicly traded international oil and gas companies.)

- Coal India 1.9 %

- Petróleos Mexicanos 1.9 %

- Russia Coal 1.9 %

- Royal Dutch Shell PLC 1.7 %

- China National Petroleum Corp 1.6 %

Yup, without big surprise, they all exploit fossil fuels (coal, gas, petrol, etc.) which are non-renewable elements, becoming more and more rare on the planet. This means this sector is eventually doomed, because at some point in the more or less near future (experts are not sure on how much fuel fossil fuels is left on Earth), humanity will not be able to exploit those resources and still make a benefice out of them. Actually, those companies risk losing more than $2tn over the coming decade on projects that will be less and less profitable.

The energy sector is changing fast and the transition to renewable energy could leave those who continue to invest in fossil fuels stranded. In other words, investors who keep their stakes in companies dedicated to fossil fuels will find that this strategy will become riskier with time, as they will eventually lose money. In order to remain competitive, fossil fuel companies have to proceed to a fundamental reassessment of their business models and seize commercial opportunities in low-carbon energy. By doing so, they can invest massively in less polluting technologies and have results quickly.

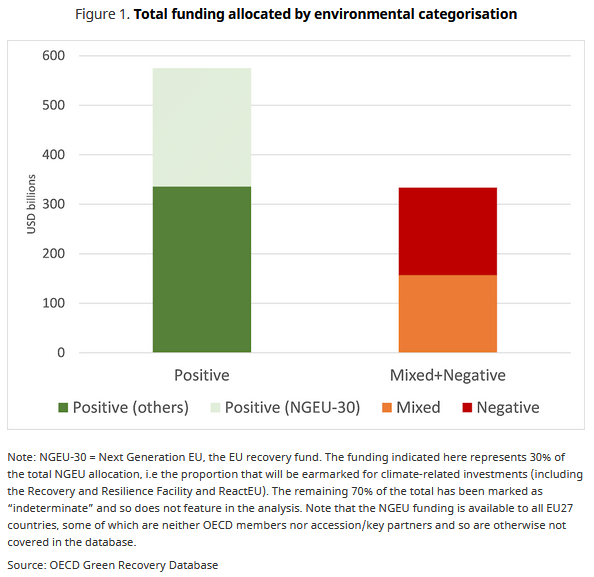

Another lever of action can be found in the CDP report. It reveals that 32% of emissions come from public investor-owned companies, making their investors key agents in the transition to a sustainable economy. These investors could make their economic support conditional for the companies, giving it only to the companies who actually comit to the decarbonization of the energy sector. For example, the French ministery of the ecological transition has a budget raise of 800 millions of euros in 2021, reaching a total of 48,6 billions of euros. With the 2021-2027 european Covid-related economic recovery plan, we are talking of 1 824.3 billion euros – which is the largest stimulus package ever financed in Europe – in order to rebuild a post COVID-19, greener and more resilient Europe. But, according to the OECD Green Recovery Database, the results of this « green new deal » are mixed: « … while USD 336 billion has been allocated towards environmentally positive measures, this is currently evenly matched by spending on measures categorised as having mixed or negative environmental impacts. Furthermore, the spending allocated to green measures represents only around 17% of recovery spending (or 2% of total COVID-19-related spending) announced by governments. The small proportion accounted for by green measures implies that, overall, recovery packages are not currently set to deliver the transformational investments needed. »

Our modern societies still massively depend on non-renewable energies. To make a big enough shift towards a more sustainable future, every part of our societies need to make amends on how we produce and consume. Regarding big companies which have to make those deeply needed changes, which parts of the industry are we ready to support like never before, and which ones are we ready to let decay and disappear?

This article was written by Noë Vaurez Diamante, Master’s student in the Muséum’s “Society and Biodiversity” specialization.

Bibliography:

- https://carbontracker.org/reports/stranded-assets-danger-zone/

- https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/nov/25/fossil-fuel-companies-risk-wasting-2tn-paris-climate-deal

- https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/2017/jul/10/100-fossil-fuel-companies-investors-responsible-71-global-emissions-cdp-study-climate-change

- https://www.ipcc.ch/

- Schleussner, Carl-Friedrich; Rogelj, Joeri; Schaeffer, Michiel; Lissner, Tabea; Licker, Rachel; Fischer, Erich M.; Knutti, Reto; Levermann, Anders; Frieler, Katja; Hare, William (25 July 2016). “Science and policy characteristics of the Paris Agreement temperature goal”

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Intergovernmental_Panel_on_Climate_Change

- http://www.c-resource.com/

- https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/recovery-plan-europe_en

- https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/fr/themes/relance-verte

- https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/the-oecd-green-recovery-database-47ae0f0d/